Dementia has no cure. But there’s hope for better care.

Cases of dementia are rising around the world, and caregivers are struggling. But families and experts are coming up with new ways to look after loved ones with dignity.

Jackie Vorhauer and her sister noticed their mother’s behavior begin to change in 2012. Nancy Vorhauer, a glass artist in her early 70s, forgot to call Jackie on her birthday. She lost her phone. She didn’t pay her bills. She made multiple copies of her keys. As Nancy’s symptoms intensified, Jackie made trips from her Los Angeles home to Millville, New Jersey, to check on her mother. One evening, Jackie arrived to find the apartment locked. A few hours later, at about 10:30 p.m., Nancy showed up with a rolling suitcase containing a stack of bus schedules, a cat toy, a broken Christmas ornament, and a handful of glass marbles—Nancy’s signature art pieces. “Hey Jack,” she said casually to her daughter. “What are you doing here?”

Nancy later told her daughters that she felt as if she had a “black hole in her memory.” It turned out to be dementia. After her diagnosis in 2017, Nancy spent four years in two different memory care units. The first tended to rely on an antipsychotic medication often used to treat behavioral problems in people with dementia. The second had some wonderful caregivers, but it was short-staffed and the caregivers lacked dementia training, says Jackie. Also, the physical space felt institutional. When Nancy wanted to go outside to the garden, the heavy doors set off an alarm.

“What you are seeing now is not sustainable,” says Jackie, 43. “It doesn’t work for people who are in memory care now, and it’s certainly not going to work for my generation.”

(What are the signs of dementia—and why is it so hard to diagnose?)

Today an estimated 57 million people globally have dementia—about 12 percent live in the United States—and cases are projected to rise to 153 million by 2050. By then, medical and caregiving costs are expected to reach $16.9 trillion worldwide. Numerous factors are contributing to the increase, most notably a growing older population; a rise in risk factors like obesity and diabetes; and worsening air pollution, which, studies show, damages brain health. Add in declining birth rates—meaning less help—and a looming crisis emerges. “It’s going to get harder and harder as the numbers go up,” says Kenneth Langa, a dementia research scientist at the University of Michigan. “We need to figure this out.”

For those living with dementia now, the priority is more-humane care. Many individuals who support people with the condition feel this deeply. They know the agony of seeing a mother struggling to speak or a widowed grandfather believing his wife will come home for dinner. They also regard sufferers as people, not a constellation of symptoms. This conviction, sparked by personal experience, is fueling a movement to scrap outdated care in favor of holistic approaches.

It’s not about dying, says Elroy Jespersen, co-founder of Canada’s Village Langley, the first large-scale “dementia village” in North America. It’s about “enriched living.” We can do this, he says, “if we just focus on the person—who that person is, who that person still wants to be, and what brings them joy.”

(Your eyes may be a window into early Alzheimer’s detection.)

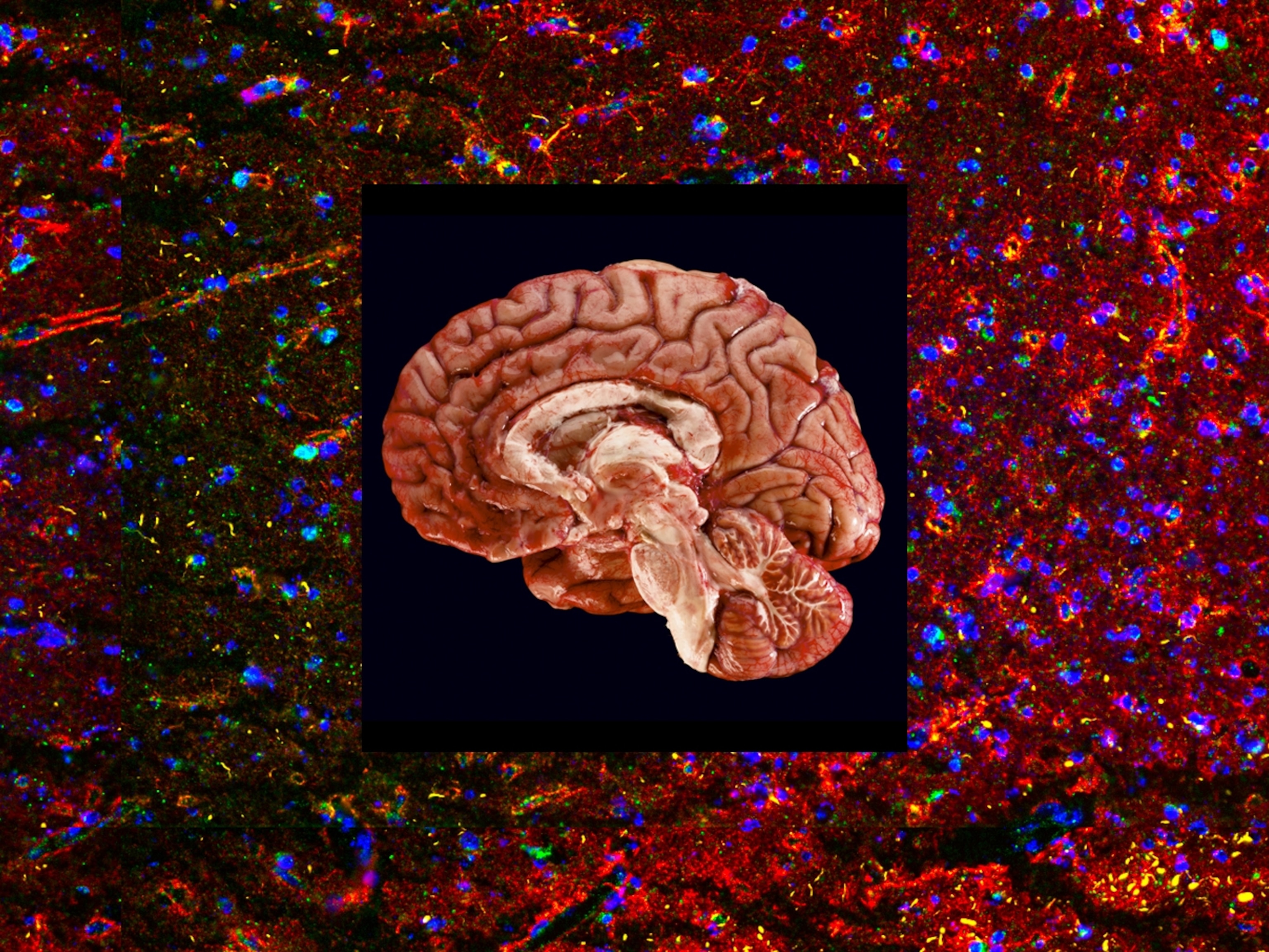

Dementia, which typically develops after age 65, is an umbrella term for numerous conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy Body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. A rare form known as dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease usually strikes between ages 30 and 50 and is the result of a gene mutation passed from parent to child. The disorders differ biologically—Alzheimer’s, for example, is characterized by brain plaques formed by a protein called beta-amyloid, while vascular dementia is brought on by a blockage of blood flow to the brain—and people can be afflicted by more than one. But the outcome is the same: a breakdown in brain cell communication and eventually brain cell death.

Memory lapses, such as forgetting someone’s name, are common as we age. These instances become a problem when they impair everyday routines—a person no longer remembers to pay the bills or becomes disoriented in a familiar environment. Such symptoms are typical of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a precursor to Alzheimer’s, or mild Alzheimer’s, the first stage of the disease. As dementia worsens, individuals become increasingly confused and may become agitated or even aggressive. Severe dementia often leads to loss of language, hallucinations, and incontinence. In the final stages of the disease, brain cell damage can inhibit core functions such as heart rate and breathing and also increase the likelihood of infection, which can be fatal.

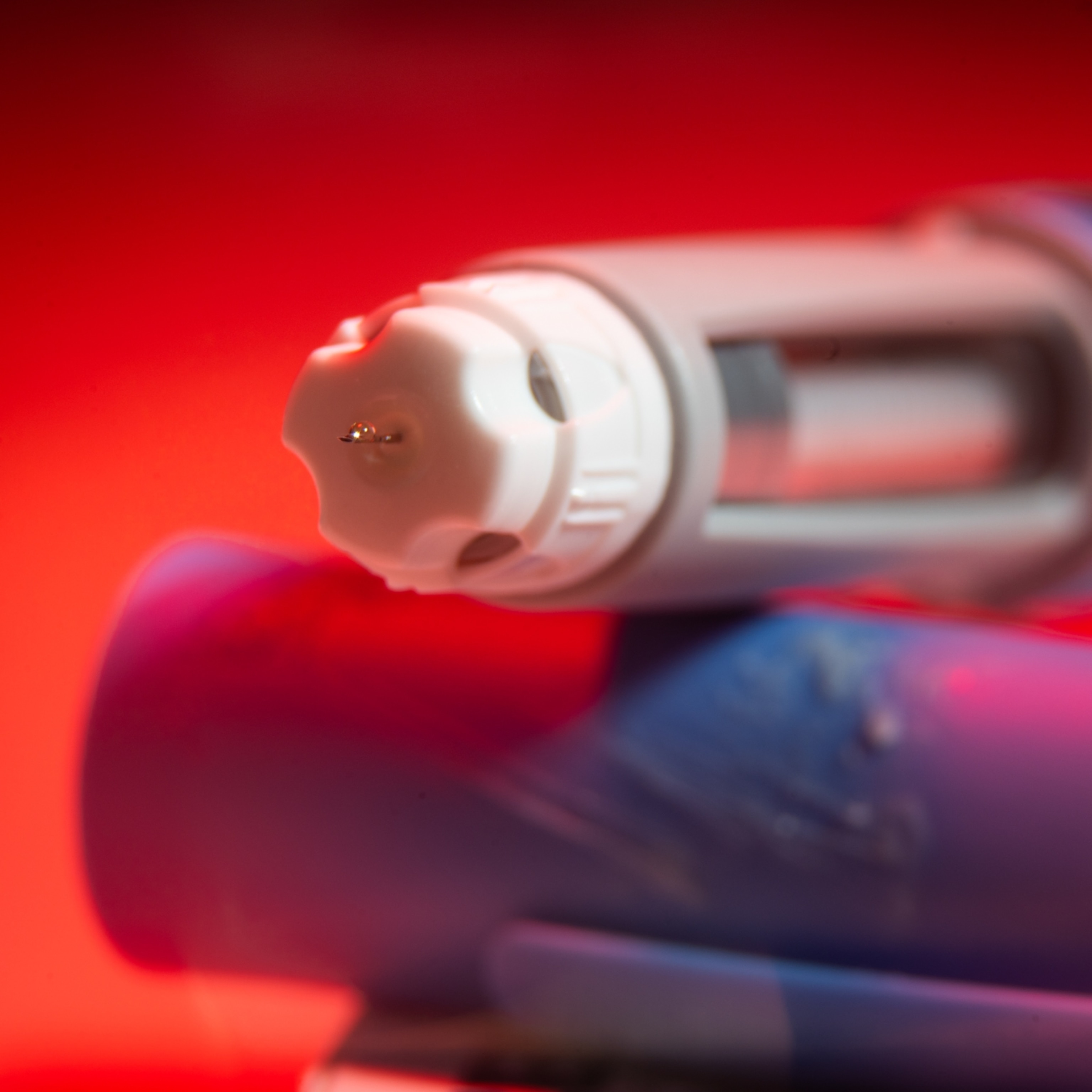

Given the complexity of the disease, dementia is inherently difficult to treat. In 2021 and 2023, respectively, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved two new Alzheimer’s drugs—aducanumab and lecanemab—the first to target the underlying biology of the disease: plaques in the brain. Lecanemab’s trials clearly show a slowing of cognitive decline in people with MCI or mild Alzheimer’s; aducanumab’s data are mixed. But neither drug is intended for other forms of dementia, they’re expensive infusions (lecanemab’s list price is $26,500 a year), and both can have serious side effects, including bleeding in the brain. “Dementia is going to be with us for the foreseeable future, even with these potential breakthroughs,” says Langa.

Traditional care prioritizes medical needs, often sidelining a person’s identity, personality, and desires. Opened in 2019, the Village Langley is rooted instead in a philosophy that applauds individual choice. Used to sleeping in until 10 a.m.? Fine. Enjoy an afternoon walk? Go ahead. There’s a barn on-site with chickens and goats, and vegetable beds for growing cucumbers and tomatoes. Jeannette Wright, a longtime gardener who has mild dementia, is especially proud of the sunflowers she planted. One tall stem arches upward, its yellow petals brightening a damp Vancouver, British Columbia, sky. “I don’t know why they grow like crazy,” says Wright, 84. “But they do.”

Research shows that social connections reduce anxiety and depression. Each of the Village’s six cottages has an open kitchen and living room with a fireplace, drawing residents out of their bedrooms to mingle. The community center houses a salon, a small store, and a café where residents can chat over a cappuccino and lemon tart. Some like to visit Cowboy, a 33-pound French bulldog that comes to work with his owner, Lisa Yarosloski, the Village’s health and wellness manager.

Natural light, which boosts mood and helps regulate sleep, is a key design element. One wall of the community center is composed of floor-to-ceiling windows. Sunshine dances off the tables and permeates the cottages, which line a main pedestrian street adorned with spruces, maples, and wisteria clinging to trellises. At one point Village staff thought about constructing overhangs for bad weather, but one of the residents disapproved. “I want to feel the rain,” she said.

After a 30-year career in senior health care, Jespersen had seen the best of traditional services up close. But when his wife’s aunt was diagnosed with dementia, he realized they weren’t good enough. There was too much regimentation, with meals at precise times and fixed activities. Jespersen especially disapproved of locked doors, which he felt contributed to residents’ agitation. “When we are focused so much on keeping people safe, we sterilize an environment and suck the potential life out of it,” he says.

Jespersen, 75, schooled himself in the Green House Project, which set out to transform the nursing home industry in 2003 when it opened its first 10-person, family-style dwellings for older residents in Tupelo, Mississippi. Since then, almost 400 Green Houses have been built across the U.S. Jespersen liked the small-scale approach, but it wasn’t until he attended a presentation about the Hogeweyk, the world’s first dementia village, located in the Netherlands, that he fully realized his vision. Designed to feel like a small Dutch town, the Hogeweyk has a central fountain, pub, and theater. Residents cook or help with laundry, which makes them feel independent and gives them purpose. That kind of freedom, says Jespersen, “is a big, big piece of living a good life.”

Weaving together threads from these models, Jespersen founded the Village Langley, which is now at capacity with 75 residents who have mild, moderate, or severe dementia. The setting pleases Jeannette Wright’s daughter, Shelley Kraan, and Kraan’s two-year-old granddaughter, Florence, who loves to visit and ride around on her scooter. “It’s a great place to live with dignity,” Kraan says.

(Dementia-friendly tourism is on the rise—here’s why it’s so important.)

To benefit as many lives as possible, pioneers in dementia care are actively sharing their knowledge. Since the Hogeweyk opened in 2008, hundreds of curious parties—from architects and clinicians to care providers and families of people with dementia—have toured the community. Similar settings have opened in France, Italy, Australia, New Zealand, and Norway. One of the Hogeweyk’s greatest draws is the autonomy it cultivates, which seems to calm aggressive behaviors. Since the village concept was introduced, prescriptions for antipsychotic medications have dropped from 50 percent to about 10 percent, says Eloy van Hal, one of the Hogeweyk’s founders. “If you keep busy in normal daily life activities,” he says, “you stay more active, and that has a huge effect on how you feel.”

Jennifer Sodo learned this lesson when her grandmother, Betty, was diagnosed with dementia. Sodo is haunted by the guilt her mother felt after she moved Betty into a senior living facility and later a memory care unit. Betty protected her family fiercely and loved baking strawberry shortcake; in memory care, she spent most of her time alone indoors. Sodo, an architect who specializes in senior living design, remembers a visit when she took Betty outside. “I saw something stir in her. She felt the heat of the sun. She could see the flowers moving, and the butterflies,” says Sodo, 33. “That little moment is what this big-picture design has to lead to. There’s a fire in me that says we can do better.”

In 2017, Sodo and her then colleagues at the architectural firm Perkins Eastman (she has since moved to a different company) visited the Hogeweyk to inform their design for Avandell, a dementia village slated to be built in Holmdel, New Jersey. Avandell’s layout is smaller and its setting more rural, but its philosophy is aligned with the Hogeweyk’s, says David Hoglund, co-founder of Perkins Eastman’s senior living practice: Create intimate living spaces that honor the simple rhythms of life—scanning the newspaper or sipping a cup of tea. Like Sodo, Hoglund, 68, understands dementia at a personal level. He lost two loved ones to the condition: his mother-in-law in 2012 and his father in 2017. “It’s one thing to talk about it. It’s another to live it,” he says.

(Why evenings can be harder on people with dementia—and how to cope.)

This mindset of honoring the person led Dementia Innovations, a nonprofit formed in 2019 in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, to conceive of a different model, which is tentatively scheduled to open in 2025. The team brainstormed with the Hogeweyk leadership and also learned that local people wanted more ownership in their loved ones’ care. The group mapped out a neighborhood of privately owned houses on 79 acres (paid for with a private donation) near Lake Michigan. Couples can remain together—a rarity at traditional memory care units unless both have dementia—and caregivers will be available at all times.

Like so many others, Chuck Butler, one of the organization’s three founders, is propelled by experience. His grandmother had dementia, but it was a conversation with a stranger when he was Sheboygan’s assistant fire chief that hit him the hardest. A man came into the fire station and began sobbing, saying he could no longer care for his wife, who had been diagnosed with the condition. Butler provided community resources, but two months later the man was back, distraught over her treatment at a long-term facility that had an exceedingly rigid schedule. “People with dementia must be able to continue their lives,” says Butler, “rather than be slowed or stopped.” He and his colleagues believe this so fervently that they named their village Livasu—a portmanteau of “living as usual.”

One of the greatest challenges of residential facilities is affordability. Because dementia is progressive and often debilitating, the costs can be exorbitant. In the Netherlands, which has socialized medicine, the price tag is covered or subsidized by government programs. But in North America, the cost falls largely on individuals. The Village Langley, a private residence, charges $7,500 to $9,000 a month. “That excludes many, many people who really could benefit,” Jespersen says. Even so, there are 150 people on the community’s waiting list.

Day programs provide an alternative for the vast number of people who are cared for at home (up to 80 percent in the U.S.), often by spouses or children who need respite. In 2018, Glenner Town Square, a 9,000-square-foot space fashioned to mimic a 1950s town, opened in Chula Vista, California. Inspired by reminiscence therapy, which aims to prompt memories by going back in time, Town Square has a vintage pinball machine and a 1959 Ford Thunderbird. Across the country, in South Bend, Indiana, a nonprofit seeking to reconfigure its day care setting received guidance from the Hogeweyk leadership. In 2022, Milton Village opened its doors, featuring a diner-style cafeteria with a jukebox, where residents can socialize at their leisure. A medical focus alone is no longer the answer, says van Hal. “We need to look at what people are still able to do.”

One day, Jackie Vorhauer got a message from an aide at her mother’s memory care unit that Nancy was refusing to eat. Jackie soon discovered the problem wasn’t her mother’s behavior: The metal fork was uncomfortable. Jackie ran out and bought a set of small, easy-to-grip utensils. “I laid the fork in her hand,” says Jackie, “and she started eating.” The lesson: Creativity is the key to better care.

Soon after Nancy died in 2021 after contracting COVID-19, Jackie set out to build a place that nourishes the spirit—a place where her mother, the gregarious artist, would have thrived. Jackie became certified in residential care for the elderly in California, and she is studying the Montessori approach to dementia and aging; a core component is using color and light to create a soothing setting. Last fall, Jackie reached out to Jespersen for guidance, just as Jespersen had reached out to van Hal. Her dream is to establish a safe, supportive, and joyful community. “It scares me to think that I would end up in a place where my mom ended up,” she says. “I’m pushing forward.”

As she sketches out her to-do list, Jackie is putting music near the top. Melodies tend to stick, even after dementia develops; researchers suspect areas of the brain that process music may be more resilient to cell damage. The late neurologist Oliver Sacks noted that personal memories may become embedded in music “as if in amber.” This appears to be the case at the Village Langley. One afternoon, Meg Fildes, a music therapist, strums her guitar and begins to sing: “Que será, será. Whatever will be, will be. The future’s not ours to see. Que será, será.” Two women hold hands and move gently to the music. When it ends, a 78-year-old woman with advanced dementia, who was once a chef and a teacher, smiles. “I love it,” she says.

(Want to keep your memory sharp? Here’s what science recommends.)

A resident of Los Angeles, Isadora Kosofsky embeds herself in the lives of those she photographs. For this month’s feature on dementia, her first for the magazine, she shadowed some 40 people over the course of three years. A TED Fellow, she gave a talk on documentary photography at the 2018 conference. Senior Love Triangle, her first monograph, was published in 2020.

This story appears in the March 2024 issue of National Geographic magazine.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

Environment

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

History & Culture

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

Science

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

- What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?

- Oral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuriesOral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuries

- How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

- Science

How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

Travel

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- How to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake ComoHow to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake Como

- Going on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboardGoing on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboard

- What to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destinationWhat to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destination