1st 'atlas' of human ovaries could lead to fertility breakthrough, scientists say

The first ever "atlas" of this female reproductive organ could be used to improve fertility treatments, scientists say.

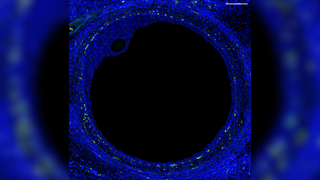

For the first time, scientists have created a comprehensive "atlas" of the cells in the human ovary and mapped the specific pattern of gene activity required for a healthy egg to develop.

The researchers determined which genes are activated in specific cells, and at what points they are activated during normal egg development, by analyzing ovarian tissue from organ donors. The key genes include those that need to be activated within the follicles — tiny sacs that hold developing eggs and release hormones — to produce mature eggs that can then be fertilized by sperm to give rise to a fetus.

Better understanding this process could pave the way for new fertility treatments, the scientists behind the research said. They described their findings in a study published Friday (April 5) in the journal Science Advances.

"This new data allows us to start building our understanding of what makes a good egg — what determines which follicle is going to grow, ovulate, be fertilized and become a baby," Ariella Shikanov, co-senior study author and an associate professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Michigan, said in a statement.

Related: Never-before-seen cells unveiled in detailed map of developing human heart

Immature versions of the follicles in the ovaries are already present when a person is born, and at that time, they collectively contain roughly 700,000 immature eggs, or oocytes. By puberty, though, many of the oocytes have already degenerated, leaving about 400,000 cells in the ovarian reserve that could potentially fully mature.

Starting at puberty, hormones prompt some of these follicles to activate and begin growing inside the ovaries each month. A handful then produce mature eggs, one of which is released into the fallopian tubes, which connect the ovaries to the uterus; meanwhile, the other activated follicles wither away, along with their eggs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To figure out what factors are needed for a follicle to release a fully mature egg, the researchers measured the activity of genes in different ovarian cells in tissue donated from five deceased, reproductive-age women. They did this by analyzing RNA — a type of genetic molecule that is used to make proteins using instructions from DNA — within the tissue.

The researchers identified distinct patterns of gene activity in the major cell types found in developing follicles, such as the oocytes and supportive cells that secrete reproductive hormones.

"Now that we know which genes are expressed [activated] in the oocytes, we can test whether affecting these genes could result in creating a functional follicle," Shikanov said. In theory, "this can be used to create an artificial ovary that could eventually be transplanted back into the body."

The idea is that scientists could someday create artificial ovaries for women who have received medical treatments that could affect their fertility, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the team said in the statement. These ovaries could be created using tissue collected from patients before their treatment and then frozen. The stored tissue could then be modified to contain follicles that are more likely to survive when transplanted back into the body, thus restoring hormone and egg production.

With their ovary atlas in hand, the team now plans to map other parts of the female reproductive system, such as the uterus and the fallopian tubes, to paint a clearer picture of how the system works at the level of single cells.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking journalism training. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)