Why kids under 5 still can't get a COVID-19 vaccine

After disappointing results from clinical trials last year, vaccine companies are working to make the shots more effective. Here's where the science stands now.

Though vaccines have restored some semblance of pre-pandemic life for most people in the United States, one group is still waiting: kids under five, who are not yet eligible for the COVID-19 vaccines. That’s been particularly frustrating for their parents, who must decide what activities are safe for their unvaccinated children—and who are often left scrambling when outbreaks shut down schools and daycare.

Compared to adults, children in this age group are less at risk for severe COVID-19. But currently the coronavirus’s Omicron variant is driving a surge in pediatric hospitalizations—more than double that of the previous peak in the fall—because it’s more transmissible than earlier strains.

Elizabeth Lloyd, a pediatric infectious diseases expert at University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, says it’s hard to tease out how many children were hospitalized for COVID-19 versus for other reasons. “But from my experience, we’re definitely seeing more kids who are sick and who are sometimes needing ICU-level care,” she says. “This is something we’re hoping with this [children’s] vaccine could be preventable.”

Emerging evidence shows vaccines can help prevent complications that kids may develop such as long COVID, or a rare multisystem inflammatory syndrome. And offering shots to the under-fives almost certainly would reduce the numbers of unvaccinated children who can spread the virus in their communities, posing a threat to vulnerable adults and creating logistical nightmares for daycare centers and parents.

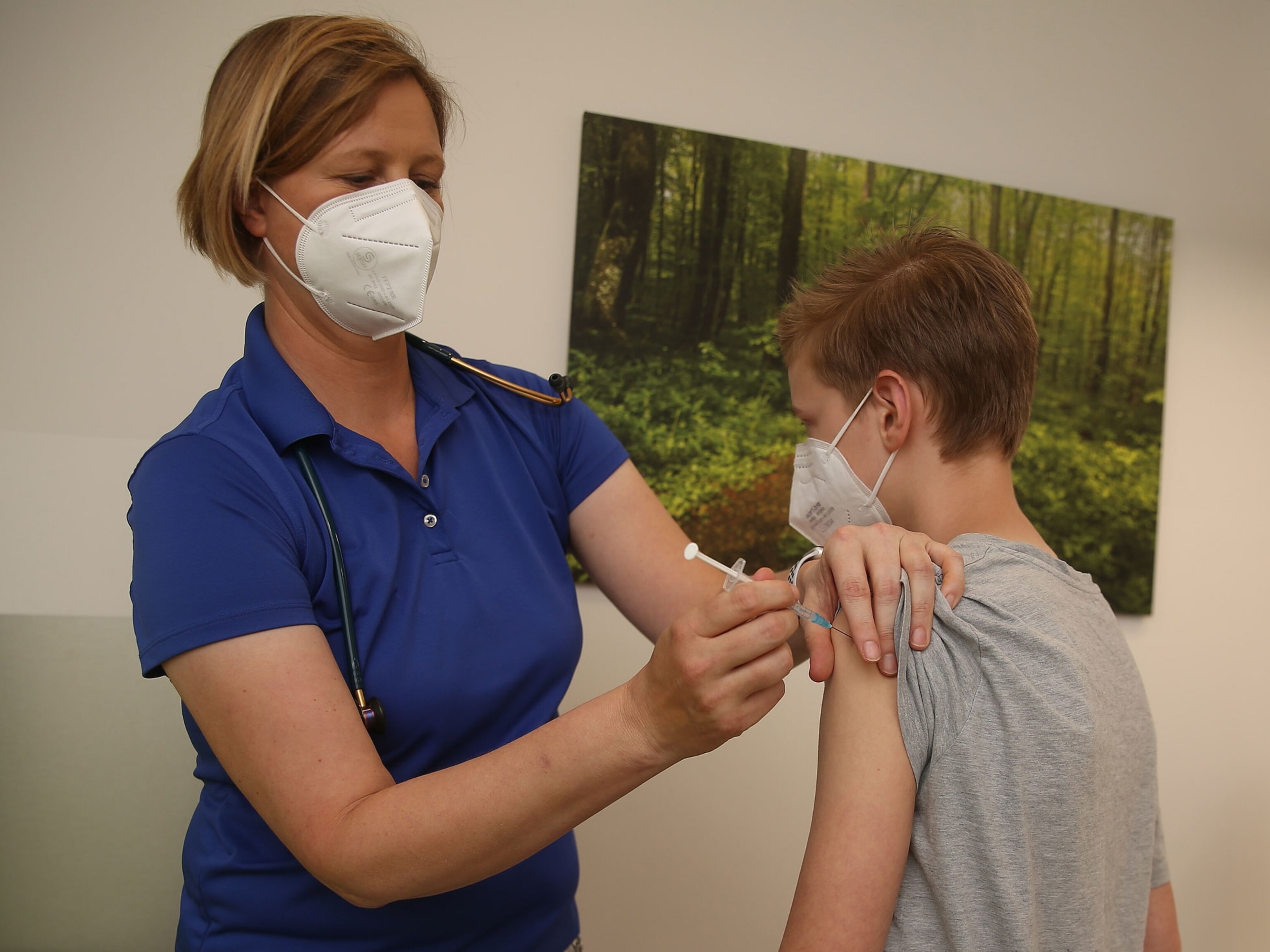

Older children have been eligible for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since early November. At that time, the expectation was that vaccines suitable for younger kids would follow shortly.

Those hopes were dashed in mid-December when Pfizer and BioNTech revealed that their clinical trials had yielded disappointing results. The companies decided to add a third dose to the vaccination series for this age group, which pushed back the timeline for authorization.

So where do things stand now? White House advisor Anthony Fauci said on January 19 that he hopes authorization could come “within the next month or so and not much later than that.” But Fauci acknowledged that vaccine availability would depend on how quickly the regulatory process moves. Moderna, meanwhile, says it won’t have study data on vaccines for kids ages two to five until March. And neither Moderna nor Pfizer-BioNTech has released any data yet.

Even in the face of all these uncertainties, Lloyd says that parents can be reassured about one thing—which is that the delays don’t mean the vaccines aren’t safe, only that the companies are still working to make them effective.

Here’s what Lloyd and other experts say about the process for approving vaccines for kids under five—and how to keep them safe in the meantime.

1. Why was the Pfizer vaccine delayed?

Pfizer and BioNTech began testing their vaccine in kids ages six months to five years in the spring of 2021—offering reason to believe that all children might be eligible for a vaccine by the end of the year. After a small dose-finding study showed that the 10-microgram dose that older children had received elicited more side effects in the younger group, the companies ultimately decided to administer two smaller doses 21 days apart.

“We weren’t hearing about any serious adverse events,” says Kristin Moffitt, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital. “But you could imagine that parents will be very carefully considering side effects from these vaccines when they’re making decisions about vaccinating their children under five.”

As recently as last fall, Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla said initial data for kids under five could be available by the end of October. But October came and went. Finally, in December, Pfizer and BioNTech announced that the vaccine didn’t generate the same robust antibody protection in kids ages two to five as it had in older populations.

While the lower dose had reduced the vaccine’s adverse effects in young children, Moffitt says it seems to have weakened the immunity generated by the two-dose vaccine.

Rather than file for emergency use authorization, Pfizer and BioNTech said they would extend their clinical trials to see if a third dose would improve results. While it’s hard to know how far off that immune response was without seeing the data, Lloyd suggests that “they must have felt that it was bad enough that if they took that data to the FDA it wouldn’t have moved forward.”

2. Why did they extend clinical trials for babies and infants, too?

What has left many parents scratching their heads, however, is why Pfizer and BioNTech also extended the clinical trials for babies and infants ages six months to two years old. According to the companies’ December statement, the low-dose vaccine was safe and did produce an adequate immune response for children under two.

It’s unclear why the companies didn’t pursue emergency use authorization for this age group. Pfizer declined an interview request for this article and referred National Geographic to its December statement for the latest updates on its pediatric trials.

Moffitt says it’s possible the companies made the decisions on trials with vaccine hesitancy in mind. For every parent who is eager to get their child vaccinated, there’s a parent who is worried about the potential side effects. Moffitt speculates that Pfizer and BioNTech might want to wait until they have more safety and efficacy data in the two-to-five-year-old population before seeking authorization for the littlest kids.

“As a provider who has had a lot of conversations with families about vaccine safety,” she says, “I can tell you that these are much easier conversations to have when you have hundreds of thousands to even millions of children who have safely received that vaccine compared to a couple of thousand, which is what we typically get from clinical trial data.”

3. What dosing regimens are Pfizer and Moderna testing now?

Pfizer and BioNTech are now evaluating a third three-microgram dose administered at least two months after the second dose. That regimen “reflects the companies’ commitment to carefully select the right dose to maximize the risk-benefit profile,” they said in a statement.

The companies did not say why they’re testing a third dose rather than conducting another dose-finding study to determine whether there might be an even sweeter spot between three and 10 micrograms. Lloyd says it might have been in the interest of getting data back faster or it could have been related to recent discussion about whether three doses is in fact the right regimen for the mRNA vaccines.

Moderna, meanwhile, is testing higher doses of its vaccine for kids in this age group. Last March, the company said it would first test two doses of either 50 or 100 micrograms given 28 days apart to kids ages two to 12. For babies and infants ages six months to two, the company would also test a 25-microgram dose. After an interim analysis, the company would select the best dosage and expand the study. But it’s unclear where those trials stand right now.

“We’re all eager to hear more,” Moffitt says. She points out that Moderna has slowed its efforts to seek authorization for older children after safety signals pointed to a higher risk of heart inflammation in young men ages 18 to 29. “I think that has subsequently held up all the age groups,” she says.

In late December, William Hartman, principal investigator of the University of Wisconsin’s Moderna pediatric COVID-19 vaccine trial, told local news station WSAW that the vaccine appears to be safe for kids under five and that results from that trial could come toward the end of January. However, the University of Wisconsin referred National Geographic to Moderna, which didn’t respond to a request for information.

4. What is the earliest a vaccine might be authorized?

Fauci has said that he hopes the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine will be authorized before March. But Moffitt thinks that assessment is optimistic. If you look at the precedent set for older children, she says, the FDA and CDC have typically taken three to four weeks to consider emergency use authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. So even if the companies submitted their data to the FDA tomorrow, it might still take a month.

And there’s no indication when that data is going to be available to submit. Moffitt says that clinical trial investigators would typically wait another month after a third dose has been administered to measure antibody responses and compile the data. She says that Fauci would certainly have the best information on when Pfizer and BioNTech expect to have that data but depending how long it takes, “we could be looking at late winter or even to early spring.”

Moderna, meanwhile, has said that it expects to report data for kids ages two to five in March and “may proceed” with seeking emergency use authorization afterward. Following the precedent set by Pfizer, Moffitt says that could mean the shot would be available as early as April.

But Moderna may have a steeper road to climb than Pfizer, Moffitt says. Pfizer has been able to secure authorization fairly quickly for younger age groups in part because the company had already amassed a large body of safety data from older groups, she explains. For example, by the time Pfizer sought authorization for children ages five to 11, it was already clear to regulators that the vaccine was safe and effective for adolescents ages 12 to 15.

“So I do worry that the lack of authorization for Moderna in 12- to 17-year-olds would potentially further delay a decision,” Moffitt says.

5. Will the kids’ vaccine take Omicron into account?

In short, no. Although there has been discussion about adjusting the mRNA vaccines specifically to target the Omicron variant, Moffitt says the clinical trial data that the FDA and CDC will be assessing are the same formulations as the vaccines that older populations have received—just lower doses. And because the clinical trials began before the Omicron variant emerged, there likely won’t be any clear data on how well the vaccine works against the variant.

6. What should parents do in the meantime?

While parents of young kids continue to wait for a vaccine, Lloyd says that one thing they can do to protect their kids is to ensure that everyone else in the household is vaccinated and boosted, if eligible. Meanwhile, everyone in the household should also follow standard COVID-19 guidance on handwashing, social distancing, and wearing masks.

Moffitt says the best mask is one with multiple layers that fits well and can be worn for a long time. She recommends upgrading to surgical masks or KN95 and N95 masks. She agrees with Lloyd that these steps are not just up to the unvaccinated.

“If everyone can be wearing a mask when they’re leaving the house, especially when they’re heading indoors in public spaces, that could go a long way toward protecting those that are not yet eligible for vaccination in a household.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads