“Of Splendid Ability”

By Kim Clarke

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

She will be the first colored lady that enters the institution.– Ann Arbor Courier, 1876

-

Chapter 1 Newsmakers

In the spring of 1880, a new work of scholarship by a University of Michigan professor began to make headlines around the country.

Alexander Winchell, a longtime geologist and paleontologist, released a 478-page book explaining the scientific origins of humankind. It was dense and meandering, filled with drawings, photographs and hundreds of thousands of words describing the evolution of the human species. He argued against the writings of the Bible, which says all men descended from Adam. No, Winchell said, there were earlier races, people with black skin, and they were inferior to the white offspring of Adam and his partner, Eve.

Winchell called these primitive people pre-Adamites. Their modern-day descendants were scattered around the world. In the United States, they were known as Negroes. And science proved – in the words and arguments of Winchell – that they would never rise to the intellectual level of white people.

“I am not responsible for the inferiority which I discover existing; I am only contemplating a range of facts which seems to prove such inferiority,” he wrote. “I am responsible if I ignore the facts and their teaching, and act toward the Negro as if he were capable of all the responsibilities of the White race. I am responsible, if I grant him privileges which he can only pervert to his detriment and mine; or I pose upon him duties which he is incompetent to perform, or even to understand.”

Elsewhere on the Ann Arbor campus, a 22-year-old student was in her final semester as a senior. Her academic focus was Latin and science, she understood German and French, and she hoped for a career as a journalist. She, too, had made news: Mary Henrietta Graham was the first Black woman admitted to the University of Michigan, and she was on the brink of graduating.

Walking the diagonal pathways of the campus, the parallel lives of Winchell and Graham would become a contrast of white and Black, privilege and struggle, and, more than anything, words and actions.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Alexander Winchell taught at several universities, with most of his career spent at U-M.

-

-

Chapter 2 Michigan-Bound

It is wrong to call Mary Graham the first African American woman to attend U-M because she was, in fact, Canadian.

She was born in 1857 in Windsor, Ontario, across the Detroit River from Detroit, where the Graham family lived in the 1850s and ’60s. Her mother, Sarah, was a white Englishwoman and her father, Levi, was a Black man born in Illinois. Ontario – then known as Canada West – was home to several communities of Black Americans fleeing slavery and oppression.

Levi Graham worked as co-owner of a Windsor grocery and Sarah Graham stayed home raising children and keeping house; Mary was the second of at least four children born to the couple. At some point, she moved to Flint, Mich., most likely as a teenager. It’s unclear if other members of her family were with her.

What is certain is that she graduated from Flint High School in 1876 and made plans to attend the University of Michigan that fall.

“She will be,” wrote the Ann Arbor Courier, “the first colored lady that enters the institution.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

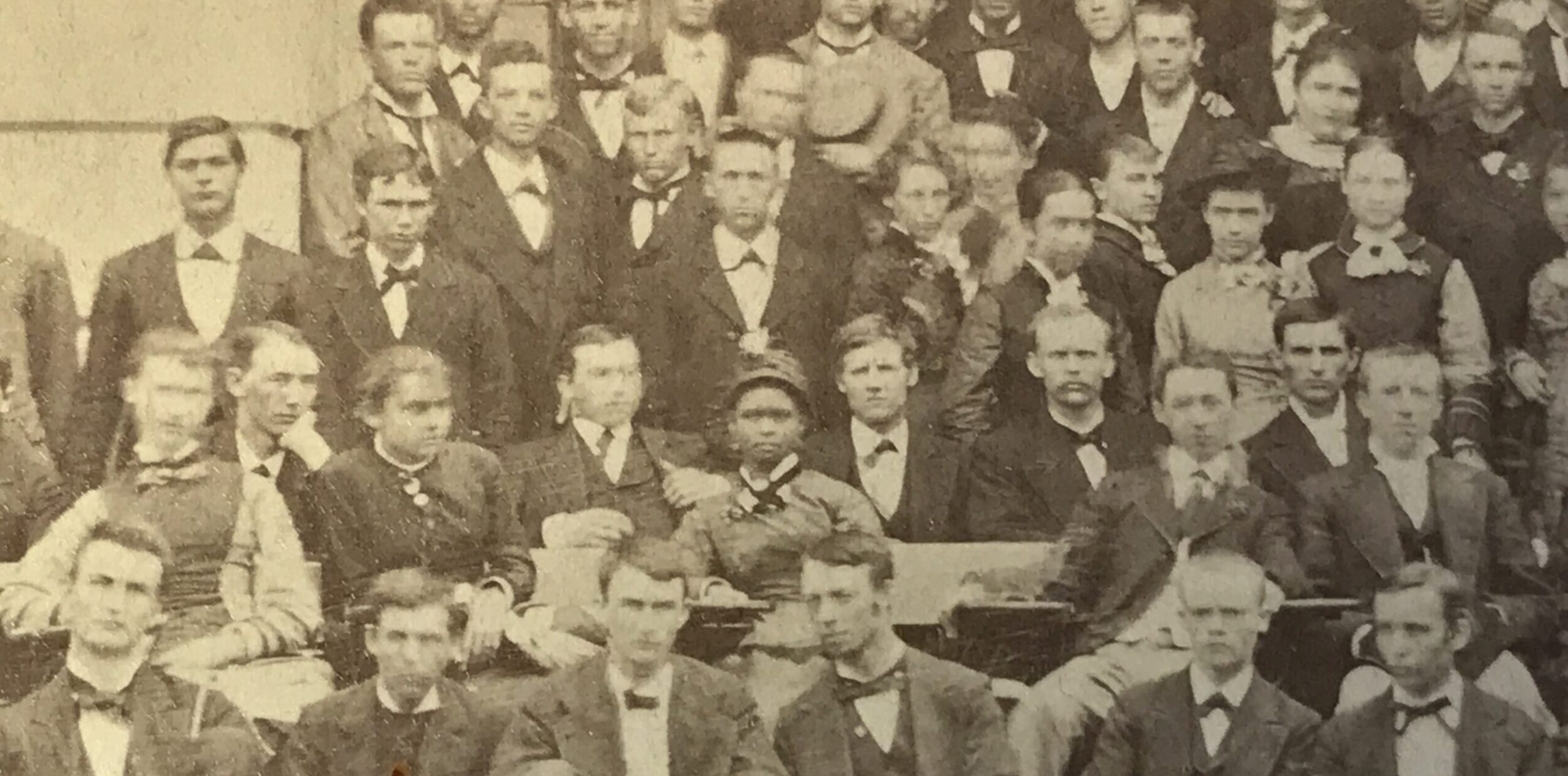

Mary Graham sits in the top row amidst her Class of 1880 peers.Image: Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan Photographs Vertical File 1850s-1980sChapter 3 Being Black at U-M

Black students were a rarity at Michigan when Mary Graham – she was known as Mollie – prepared to enroll. The all-white, all-male campus had only started to change in the late 1860s, and ever so slowly.

“The Negro is knocking for admission to our colleges,” wrote student editors of the University Chronicle in 1868, “and in a few of the institutions, the portals have been thrown open and this stranger admitted.”

With slavery abolished and the Civil War ended, African Americans looked to obtain educations that, for many, had been illegal, substandard or simply out of reach. Fewer than 50 African Americans had graduated from American colleges before 1865. Reconstruction saw the founding of Black colleges and universities in the South: Fisk, Howard, Morehouse and Hampton Institute. Closer to Ann Arbor, two Ohio institutions – Oberlin College and Wilberforce University – had been educating African Americans since the 1850s.

Oracle writers voiced concern for African American students seeking an advanced education. First there would be prejudice and “obstacles thrown in his way by his fairer compeers.” And Black students would be held to a higher standard than whites, with the slightest failure pointed to as proof they were unqualified to attend college.

“If he takes prizes in discussions, if he exhibits his progress at Junior Exhibitions and receives showers of bouquets and storms of applause at commencement, he will be pronounced a decided success as a student,” editors wrote.

“On the contrary, if he is found to be negligent in his duties; or if, having been insulted by some young blood, he should so far forget his station as to knock down the aggressor, and therefore, be expelled from the institution, the committee will decide that his mental power is not great enough to overcome the classics and higher mathematics.

“It will be an easy step from such a conclusion to the similar one that he cannot learn, and therefore should not be instructed. Then will the shovel and the hoe, the field and the log cabin be his inheritance forever.”

It’s believed the first African American to attend U-M was Samuel Codes Watson, who enrolled in 1853 but transferred before graduating. It was later learned that Watson was of mixed race and passed as white; as a student, his skin color was never recorded. That physical recognition came with the admission of law student Gabriel Franklin Hargo in 1868.

“Soon after the commencement of lectures, an ‘American citizen of African ‘scent,’ made his appearance … and demanded to be matriculated. He answered to the euphonious appellation of Gabriel Franklin Hargo, and hailed from Adrian, in this State,” noted the student-written Michigan University Magazine. “We believe it is the first time that a person of that complexion has ever entered this University, and as such, the fact deserves to be recorded.”

-

Chapter 4 Professor Winchell

In the decade when Black students began to populate U-M and young Mollie Graham was attending high school, Alexander Winchell was an academic nomad.

After 19 years of teaching at Michigan, where he had established himself as an excellent orator, prolific writer and noted scientist as well as an opponent of President Henry P. Tappan, he left Ann Arbor in 1873 to become the first chancellor of Syracuse University. It was an ill-fated appointment; where Winchell wanted to focus on research, the chancellorship required him to devote time to raising money, and he resigned after all of 18 months. He then joined the Syracuse faculty as chair of the geology program. At the same time – 1875 – he accepted a faculty appointment at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and divided his time between Tennessee and New York.

Vanderbilt was not Winchell’s first stay in the South. Before he joined the Michigan faculty in 1854, he had spent three years in Alabama’s Black Belt, so-called both for its rich soil and the slaves who worked it, leading several high school-level institutes. During the Civil War, he took a leave of absence from U-M to manage a Louisiana cotton plantation in Union-controlled territory, using the labor of freed Black people. The enterprise failed.

He had seen African Americans enslaved, and later as free women and men. His views of them never changed, as evidenced by his writings.

“In respect to activity, industry and enterprise, the habits of the Negro have not improved with his improved freedom and self-dependence,” he wrote. “In slavery, coercion prompted some to regular occupation, however inefficient; in a state of liberty, the Negro exercises his right to live in idleness until he becomes the abject slave of want.”

It was at Vanderbilt that Winchell’s views on evolution and the Bible began to cause problems. In 1878 he published a pamphlet, “Adamites and Pre-Adamites,” a 50-page precursor to his weightier 1880 book. It did not sit well with the trustees of Vanderbilt, a Methodist institution that held firm to the Bible’s explanation of mankind’s origins in the Garden of Eden. Vanderbilt fired Winchell, and he returned to Ann Arbor for good.

-

Chapter 5 “Of That Persuasion”

Like the other graduates of Michigan’s handful of certified high schools, Mary Graham qualified for automatic admission to U-M.

“Miss Mary Graham, a young colored girl, who graduated from the Flint High School last month, intends entering the University next fall,” shared the Fenton Independent. “She is the first applicant of that persuasion.”

She was proficient in English, French, mathematics, history and all other required subjects. Her enrollment papers were signed with a flourish by “J.B.A.” – President James Burrill Angell. The date was Sept. 21, 1876 – the first day a Black woman was admitted as a Michigan student.

Looking around campus, Graham would have seen a sea of nearly 1,100 white student faces, plus an all-white, all-male faculty. At the end of her freshman year, if she had thumbed through the 1877 Palladium – a yearbook published by fraternities – Graham would have seen how most viewed a Black person’s place at U-M: A sketch depicting that year’s senior reception shows young white students arm-in-arm and dancing. An orchestra plays in the corner and decorations festoon the crowded room. The only Black faces at the party are those of servants – men serving drinks and hors d’oeuvres to the white party-goers.

There is little evidence of Graham’s life as a student. Records show she stood 5 feet tall, weighed 140 pounds and wore her dark hair braided and pulled back. She put on earrings for any photographs she appeared in.

She lived in Ann Arbor with mother and sisters at a time when there was no on-campus housing and students lived in boarding houses or with relatives. She belonged to no student organizations that were open to women, such as the Student Christian Association, Literary Adelphi and the Junior Eating Club. She did not join the all-women’s Quadrantic Circle.

Perhaps she was shy. Perhaps she embraced the motto of her graduating class: “Modest Eighty.” Perhaps it was easier to succeed by keeping a low profile, if that were possible, as the only Black woman in the room.

We know she was a good student. In Graham’s day, faculty leaders maintained an oversized journal of official business of the College of Literature, Science, and Arts. Here, professors would scribble the names of students who came before them for permission to alter their studies. Students would ask to drop courses. They would seek approval to make up class time because of illness. They would request to postpone senior theses because, well, they just needed a few more days.

Professors would consider the pleas and document them in the ledger as approved or denied. Most requests, for the record, were rejected.

Not once in her four years did Graham ask for special consideration. No delays, no postponements, no excuses. The only time her name appears in LSA records is among the students approved by faculty for graduation in June 1880.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Winchell's book provided depictions of races he described as inferior to white people.Image: Preadamites: or, A demonstration of the existence of men before Adam, by Alexander WinchellChapter 6 The Pre-Adamites

Winchell returned to Michigan in 1879, just as Mollie Graham was beginning her senior year. As she entered her final months of study, his tome – The Pre-Adamites or, A Demonstration of the Existence of Men before Adam – made its way to the printing presses. It would become Winchell’s bestselling work, with five editions printed.

In an era when Charles Darwin was upending the understanding of human origins, Winchell took a different approach and advanced a theory of human evolution known as pre-Adamism – that there were humans on Earth before God created Adam, as written in the Bible. These pre-Adamites, while also created by God, descended from unknown parents and were inferior – physically and intellectually – to the offspring of Adam and Eve. (Winchell was fickle on describing Adam’s skin tone. He was dark-skinned, but it was a ruddy Mediterranean characteristic that, with descendants, then branched into “Blonde and Brunette and Sun-burnt subdivisions” not found in the black race, Winchell wrote.)

He argued for using anthropology, ethnology and archaeology – in addition to scripture – to explain the origins of human life. Different races, he wrote, had different beginnings and evolved in diverse ways. He pointed to supposed discrepancies in lung capacity, cranium size, arm length, chest circumference, skin texture and more.

“Every race and every condition is characterized by some degree of intellectual activity, by some form of manifestation of the social sentiments, and by some degree of a moral and religious consciousness. But races differ both widely and ineradicably in the relative strength and influence of the powers of the soul,” he wrote.

His rhetoric about Black people, in a chapter titled “On the Inferiority of the Negro Race,” was a racist diatribe. The notion of an educated Black person, to him, was preposterous.

“No American Negro,” he wrote, “has ever produced any original work in mathematics or philosophy; the imaginative and aesthetic powers are similarly dormant; poetry, sculpture, painting, owe almost nothing to Negro genius … To the present hour, the Negro has contributed nothing to the intellectual resources of man.”

As for accomplished African Americans such as poet Phillis Wheatley, sculptor Edmonia Lewis, and congressmen Hiram Revels, Blanche Bruce and Joseph Rainey, Winchell argued they surely had “some infusion of Caucasian blood” to account for their successes.

Did Alexander Winchell and Mollie Graham ever cross paths on the U-M campus? Did she read newspaper accounts of his new book? Did he eye her with contempt or suspicion while she sat in a classroom or studied in the library?

It’s unknown. In their one and only academic year together, he taught four classes in geology. She was required to take one science course, and would have had the option of electives in zoology, botany and Winchell’s specialty, geology. But his papers do not dwell on his classroom connections with students. And no record exists of her class schedule.

It is known that when Graham graduated, with a bachelor’s of philosophy degree, the Ann Arbor Courier praised her accomplishment. “She has proven herself to be a person of unusual intellect, and is entitled to much credit for her perseverance in pushing her way through the university.”

To Winchell, the notion of an educated Black person was preposterous.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The campus of the Lincoln Institute in Jefferson City, Mo.Image: Lincoln University ArchivesChapter 7 “An Accomplished Scholar”

Immediately after commencement, Graham was hired as a teacher at Missouri’s Lincoln Institute (today Lincoln University), a teaching college for Black students founded after the Civil War by Missouri regiments of the United States Colored Infantry. She was among the initial appointments of Inman E. Page, the first African American to lead the school and an educator who vowed to hire Black teachers to teach Black students.

Within a year, she was promoted to matron, in charge of some 60 young women at the Institute. “A great revival is now in progress there for the success of which she desires the prayers of our Association,” wrote U-M’s Student Christian Association in 1881.

After two years in Missouri, Graham was ready for the next chapter of her life. She returned to Ann Arbor to marry Ferdinand L. Barnett Jr., the son of a former slave, a graduate of Northwestern University, and a politically active Chicago lawyer. The two had known each other for several years, and it’s possible they first met as children; the Barnett family, like the Grahams, had moved from the United States to Windsor, Ontario, when he was a child.

(One of the witnesses to their marriage was Sophia B. Jones, a fellow Canadian who in 1885 would become the first Black woman to earn a U-M medical degree.)

In addition to practicing law, Graham’s new husband had founded The Conservator, Chicago’s first African American newspaper, and was president of the National Colored Press Association. He had campaigned vigorously for the capitalization of the first letter of his race – Negro – to signify respect.

The couple made their home in Chicago.

“Mrs. Barnett has the reputation of being an accomplished scholar, a clever musician, and an agreeable lady,” said The Conservator, “and her advent in Chicago social circles will be hailed with pleasure.”

Indeed, she threw herself into the upper echelon of African American life in Chicago, where the Black community was small – less than 2 percent of the population in 1880 – but vibrant. She was an alto who sang in the choir at St. Thomas Episcopal Church alongside her husband. She taught Sunday school. She belonged to the invitation-only Prudence Crandall Club, a literary group established by her friend Samuel Laing Williams, an 1881 U-M graduate and her husband’s law partner, and became its secretary.

(The club’s namesake was a white Connecticut abolitionist who opened an academy for African American girls. “[Its] members were a tight-knit well-educated group, and the club format included posh social gatherings and classical readings,” writes historian Wanda A. Hendricks.)

Graham Barnett became a mother and also went to work at her husband’s newspaper, starting in the typography room setting the letters that made up the paper’s text. She soon wore other hats: proofreader, mailing coordinator and, in 1888, editor in chief.

In the eight years since leaving Michigan, where she said her professional goal was to be a journalist, she had become part of the Black elite in the country’s second-largest city.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Chicago's Inter Ocean newspaper shared Barnett's death on Jan. 4, 1889.Image: Inter Ocean newspaperChapter 8 Legacies

It ended too soon. Mary Graham Barnett died suddenly in 1889, on the second day of the new year, of what was believed to be heart disease. She had been ill a year earlier, but her death at 31 came as a terrible loss. Family and friends were “shocked almost past endurance,” wrote a Chicago paper.

“No woman in Chicago was more useful in many ways and more beloved and appreciated,” said the city’s Inter Ocean.

At the Bentley Historical Library, an obituary in Graham Barnett’s file – most likely prepared by a family member – reads:

“At the time of her death, she was in the prime of useful vigorous life, the blow coming without a moment’s warning … During her short career of usefulness, she had come to be regarded not only as a woman of highest moral integrity, but of splendid ability and brilliant promise.”

She left behind her husband and two young sons, Ferdinand III, 4, and Albert, 2. The children would have a new mother in 1895, when Ferdinand Jr. married Ida B. Wells, a crusading journalist who documented the epidemic of lynchings and helped found the NAACP.

Alexander Winchell died two years after Graham Barnett, at the age of 66. “A great scholar has passed from earth,” wrote the Ann Arbor Argus. “A master mind is gone.”

His name, and his views of Black people, however, would live on.

Winchell’s “science” was adopted by white supremacists. In 1900, Charles Carroll wrote a vicious anti-Black screed called “The Negro a Beast,” repeatedly citing the claims of Winchell – “the great American scientist” – and others who promoted the theory of pre-Adamites.

In particular, Winchell’s chapter “On the Inferiority of the Negro Race” would come to be used by the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazi groups. It found new, extended life with the internet and the hate website Stormfront, a forum popular with white nationalists.

As he did throughout his life, Winchell made headlines, again, in 2017.

A U-M undergraduate asked that Winchell’s name be removed from West Quadrangle residence hall, where it had been in place since 1939. That year, for reasons that were never announced, the U-M Board of Regents affixed Winchell’s name to a “house” within the dorm, one of several floors named for past faculty members. “It is a little known fact,” Kevin Sweitzer wrote to President Mark Schlissel, “but it is a fact nonetheless, that Professor Winchell was a supporter of biologically based white supremacy.”

A review committee of U-M faculty, including several historians, agreed. “Because Alexander Winchell’s work was out of step with the trajectory of modern science in his own time and with the University’s own aspirations in those times as well we see no reason for his commemoration in a named University space,” the faculty wrote. “Our society depends on its history and because it does we should remember everything. But our choices about what we commemorate must reflect our values.”

A year after Sweitzer’s request, Schlissel asked regents to erase Winchell. The vote was unanimous: Alexander Winchell’s name would be stripped from West Quad.

As for Mary Henrietta Graham, her name adorns no room or building at her alma mater.

Sources: Report and Recommendations on Alexander Winchell Name in West Quad, President’s Advisory Committee on University History; Preadamites; or, A Demonstration of the Existence of Men before Adam, by Alexander Winchell; College of Literature, Science and the Arts records, 1846-2017, Bentley Historical Library; Mary Henrietta Graham necrology file, Bentley Historical Library; “A Chapter in the History of Academic Freedom: The Case of Alexander Winchell,” by Mary Engel, History of Education Journal (1959); Adam’s Ancestors: Race, Religion, and the Politics of Human Origins, by David N. Livingstone; Fannie Barrier Williams: Crossing the Borders of Region and Race, by Wanda A. Hendricks; Ida: A Sword Among Lions, by Paula J. Giddings; A Centennial History of Lincoln University, 1866-1966, by Albert P. Marshall; Key Events in Black Higher Education, The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education; contemporary newspaper accounts