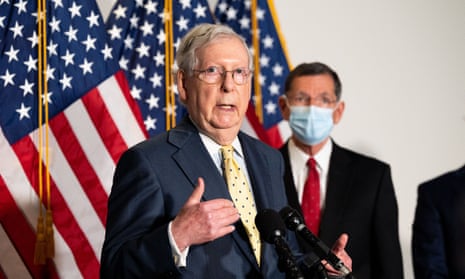

The 31 million Americans struggling with unemployment today are not a whit less desperate and fearful now that Mitch McConnell’s “skinny” Covid-19 relief bill failed to pass the US Senate. Thursday’s performative theatrics did little more than provide cover to vulnerable Republicans and add one more day to the now six weeks since Senate Republicans refused to extend the extra $600 in Covid-related weekly jobless benefits. With McConnell sounding all but liberated from any more pressure to show compassion before the election, and the media’s attention pinned to shinier Trumpian objects, it is even more imperative to refocus on the crisis at hand and to dig beneath the hollow excuses for such demonstrable indifference on the part of lawmakers. It is time to find an answer to the question: how is such unnecessary suffering justified?

According to the Republicans, the aid is “too generous” and “disincentivizes” the unemployed from seeking work. So perverse are the effects of these benefits, they argue, that it is actually workers gaming the system who are slowing the economic recovery, not the Covid-driven loss of millions of jobs.

That these charges persist despite significant evidence to the contrary testifies to the power of the conservative creed that few things in life are more perilous than excess government compassion: “unearned” income such as unemployment benefits perversely undermines recipients’ self-discipline and willingness to work, leaving them even worse off. It is a self-evident truth of human nature, conservatives avow, that relieving the suffering of those in need induces dependence and indolence, whereas deprivation incentivizes labor.

Here’s the secret sauce: since that which is “self-evident”, such as ideas about human nature, can be neither proved nor disproved, such truths are conveniently immune to debunking evidence. Thus they persist.

They should not, however, be immune from being called out for their stunning inconsistency. In 2017 these same Republicans trumpeted a radically different truth about human nature when they pronounced that cutting taxes on the wealthy would incentivize them to work harder, invest more and spur rapid economic growth.

But how is it that extra money incentivizes the rich to become paragons of moral virtue and economic rainmakers, whereas for working people it incentivizes them to become social parasites and economic saboteurs? How can there be one human nature for the 1%, and another for the rest of us?

It’s a question too rarely asked. So deeply rooted in Anglo-American political culture is this bifurcated view of human nature that it’s treated almost like natural law. In fact, it’s a product of history, originally designed to solve a problem not unlike our own, and tied to the early capitalist need for a new industrial workforce.

In the last decades of the 18th century, the English upper classes revolted against the tax burden of the centuries-old system of poor relief – so named not because it was welfare but because “the poor” were simply those who had to work for a living. As protection against cyclical structural unemployment, its recipients bore no stigma, and access to its benefits was considered a right.

When the need for jobless benefits escalated under the pressures of early industrialization, angry taxpayers found an advocate in Thomas Malthus, who turned centuries of social policy on its head by asserting that poverty was caused not by systemic unemployment but by government assistance itself. Providing the template for today’s Steve Mnuchins and Lindsey Grahams, he explained that aid to the jobless perversely incentivized them not to seek work.

Malthus based his argument on a novel view of human nature: society consisted of two “races”: property owners and laborers. While the first embodied the high morality of Enlightenment rationality, the latter were not moral actors but motivated only by their biological instincts. When hungry, they were industrious; when full, they lazed. They did little more than think through their bodies.

As in the natural world, maintaining chronic scarcity was the necessary motor of the whole system. Since the pangs of hunger alone disciplined the poor to work, if you remove that scarcity by “artificial” means – and nothing was more artificial than government assistance – the incentive to work dissolves. But it was not enough to simply abolish public assistance, although Malthus is rightfully credited for his role in doing just that. He also railed apocalyptically against reducing scarcity through charity. Society’s very future depended on the unemployed being fully exposed to the harsh discipline of the labor market.

Malthus’s enduring contribution to social policy was thus to make hunger the virtuous suffering that underpins a productive workforce, and “too much” the virtuous luxury that unleashes the social contributions of the rich. Armed with these two views of humanity – the rich depicted as noble paragons, the poor as inherently indolent and parasitic – conservative social policy continues to declaim the unfounded “truth” that a strong economy depends on inflicting pain on workers while providing government largesse to the rich.

The most recent iteration began with Reagan’s massive tax cuts in tandem with his attacks on “welfare queens”. It continued through the derisive conservative trope of “makers and takers” to Mitt Romney’s infamous “47%” of “entitled” “tax shirkers” to former House speaker John Boehner’s 2014 claim that the jobless think “I really don’t have to work … I’d rather just sit around” to today’s tax-cutting Republicans, who announced that they will extend jobless benefits “over our dead bodies”.

To be sure, today’s policymakers would be hard pressed to name the Malthusian roots of their belief in the perils of compassion. But that makes it no less urgent to expose their policies as based on nothing more than historical fiction. For there is a darker message lurking within this view of human nature: Reducing working people to their bodily instincts robs them of their moral worth and, as we know from how our “essential” workers have been treated, makes them utterly disposable.

Margaret Somers is Professor of Sociology and History, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Her most recent book, co-authored with Fred Block, is The Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi’s Critique (Harvard, 2016)